My Chicago Symphony job was not what I thought it would be

Be ready for anything

I arrived early for my first rehearsal with the Chicago Symphony in 2002. It was a strange time to start the job: June, the last two weeks of the season, with Music Director Daniel Barenboim on the podium. By that time of year, most orchestras have seen just about enough of their Music Directors, while the Music Directors themselves realize that the sand is running out of the hourglass: they’d better make their criticisms stick, or the orchestra is going to come back after the summer just as lousy as they were before!

The program that first week was a single piece, unfamiliar to most of us on stage. Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius had apparently been on Barenboim’s bucket list for quite some time, and this was his chance to cross it off. I wished for something less ambitious for my first week on the job. The second violin part didn’t make any more sense to me on stage at Orchestra Hall than it had in my new apartment the day before.

As I sat sawing away, concertmaster Robert Chen crossed the stage to welcome me to Chicago, or so I thought. A mentor of mine from my school days in Philadelphia, he was one of only a few familiar faces there. In fact, he was giving me fair warning: that I might be asked to sit on the first stand for the opening rehearsal!

“Wait…why?”

“Barenboim likes to see the new faces right away. It may happen, it may not. Don’t worry. Just be ready for anything.”

I made a note not to worry, then began to worry about what anything might entail.

“Wait, doesn’t that mean sitting with—“

The principal of the section was about to retire. In fact, the orchestra had already held two auditions for his position, and he was to leave as soon as a successor was found. Since I had taken both of those auditions, and had not been offered his position, it was a reasonable assumption that some people on the audition committee weren’t big fans of my playing. Apparently he was one of them.

Robert interrupted, “He doesn’t like your playing. So what. Everyone doesn’t have to like you, Nathan. Get used to it!” He crossed back to first chair wearing a smile. I had no choice but to put one on as well.

As ten o’clock approached, and the empty seats filled in, I wondered whether I might be spared the extra scrutiny. But just before the hour, I saw the principal rise from his chair and walk directly back to me. He invited me to share a stand with him that morning.

The idea had obviously come from up above, but somewhere along the chain of communication, a link had been skipped. The assistant principal, whose seat I would be taking for the morning, was unaware of the game of musical chairs. As I approached, he looked at me as he might an encyclopedia salesman who had interrupted his dinner. We would have to patch things up later.

The principal turned out to be a perfect gentleman and a classy violinist. This was more or less the last hurrah for him, and he could have hazed me without repercussion. But instead he pointed out a few tricky spots and made sure I knew what line of the divisi to play. Did I sense, even in the grizzled veteran, apprehension at the prospect of reading this vast Elgar work under the baton of the music director?

A winning attitude

Then, in a rush, Barenboim strolled onto the podium, the tuning A sounded, and we were off! Although I had been a professional for two years, I had never played (not even as a substitute) with a giant symphony orchestra like Chicago. I experienced sensory overload: the mercurial conductor swaying above me, cryptic notes in front of me, unknown colleagues all around. My bones shook from the sound waves. At the biggest moments, of course, the famed Chicago brass supplied enough power to light the hall. But every section of the orchestra pulled its weight: each player was trained to produce maximum sonic energy without crossing the line that divided class from crass.

What surprised me most, once I got my head out of the music stand, was the attitude of my new colleagues. In my previous orchestral experience, as soon as two interlocking lines began to separate, there was a whiff of panic in the air. I might exchange fretful glances with those in my line of sight. But in Chicago, there was barely any acknowledgement of untidiness. Notes and rhythms flew in all directions, and it was a rare measure that was truly perfect in that reading. But it was clear to me that everyone on stage fully expected things to sound better at the next rehearsal, still better the one after that, and so on through the performances. I marveled at the collective confidence, while remaining terrified that I would be the one to step in a rhythmic trap!

Keep it clean

The following day, I moved back to my assigned seat near the back of the second violins. I began marking some fingerings in the toughest passages. Since I was sitting on the audience side, or the “outside” of the stand, my markings went above the notes. At least that’s how things had always worked…

As I put in my first set of numbers, my stand partner made a sound, a kind of groan cut short. I looked over, the point of my pencil still on the page. “Did you want my markings on the bottom instead?”

“We don’t mark fingerings here,” he said.

“Here, you mean at this spot?”

“I mean in this orchestra.” His face softened, and he added, “Sorry, you’re probably used to seeing them, right?”

I was indeed used to seeing fingerings as a matter of course. My mind was fairly blown.

“How do you play all this music then?”

My stand partner paused, as if he’d never considered the question before.

“Practice?” he suggested.

When you ask, be ready for the answer

Adjusting to life in the big symphony wasn’t my only concern that first week. There was a cloud looming over the Elgar: I was to play yet another audition for principal second violin that weekend. After twice failing to win that spot, I was determined to impress the committee this time. But it was not to be: after several performances of Gerontius, I was drained. I felt out of sorts the entire audition. Had I wanted the spot too much? Not enough? Had I peaked too soon, or not at all?

My performance was best summed up by Robert when I asked him for feedback the day afterward. “Which number were you? Hmm. I wrote down, ‘Sounded wiry.’ What violin were you playing?”

“The Strad.” At the time, one was on loan to me.

Robert responded with a line every violinist hopes to hear, but only if they’re playing a cheap factory violin: “How did you make it sound like that?”

The orchestral hamster wheel

And with that, the downtown season was over. In one week, the Chicago Symphony would move twenty-odd miles north, to its summer home at the Ravinia Festival. I used the free week to decompress: from moving to Chicago, meeting a hundred new colleagues, taking an audition. I should have set aside at least some of that time to fortify myself against the avalanche of music that was about to bury me.

I realized my mistake as soon as I arrived for the first Ravinia rehearsal: my folder bulged with parts for that week’s three full programs. From my school days, and even from my weeks so far in Chicago, I was accustomed to at least four rehearsals for a full orchestral concert. But looking at the Ravinia schedule, two was the maximum; one was more common. A single-rehearsal program is really just a read-through plus a concert. And in some cases, even the read-through was optional!

One performance that summer featured Gershwin’s suite from An American in Paris. I can’t recall the remainder of the program, but our conductor must have thought it very difficult since he left no time at all for the Gershwin. As the personnel manager strode onto stage, ending the rehearsal, I looked around, bewildered. Everyone was heading down to the locker rooms, but we hadn’t even looked at the Gershwin! Were we cutting it from the program?

I can’t bring to memory which conductor it was who was so discourteous to Gershwin, but I clearly remember someone in the locker room muttering, “The only downside to not rehearsing with him is that we won’t know how he’s going to screw it up in advance. Be ready for anything, I guess.”

There was that line again. I was still concerned, however. “I could have used at least a run-through. I’ve never played it before!” I cried, unaware that I had set myself up for the oldest joke in the orchestral book.

Five guys turned at once, shouting in unison, “You’ll love it!”

Just one of the guys

One program in particular seemed to go beyond the bounds of decency for a violinist: a first half consisting of two Strauss tone poems (to paraphrase Ulysses S. Grant, one was Don Juan and the other one wasn’t) and a second half of three Wagner overtures: Lohengrin, The Flying Dutchman, and Tannhauser.

The single rehearsal didn’t offer much comfort. Despite my meticulous preparation for this obvious killer program, notes seemed to fly out from underneath my fingers. Phrases bobbed and weaved while I tried to keep them centered in my sights. So I made it my mission that afternoon to be 100% ready for the evening show. In my zeal, however, I went overboard. I have a vague memory of heavy eyelids during the first half, then after an intermission coffee, a spent and shaky bow arm.

Descending to the men’s locker room, I heard the voice of David Taylor, one of the orchestra’s assistant concertmasters. A veteran of the Cleveland Orchestra before coming to Chicago, he had seen and heard it all. He was exhilarated rather than exhausted by the Strauss and Wagner. “Boy, that Tannhauser! What a monster! Can you remember the first time you saw that on the stand in front of you?”

“Yeah, I can. It was twenty minutes ago!” I answered. I had won my first locker room laugh.

As I changed back to street clothes, I caught sight of the peculiar knob on the wall that controlled the volume of the stage monitors. It turned from 0 to 10. If you were fortunate enough to be “off” one of the pieces on a program (rarely a violinist’s lot), the monitors were your lifeline, for they allowed you to hear when you’d be needed back up on stage. A printed warning adorned the knob’s enclosure: “Volume must remain high”. Next to this, one of my colleagues (surely a beaten-down string player) had penciled in block letters, “I’m playing as loud as I can!!!”

Desperate times call for extraordinary overtime

The monitors carried messages from the personnel office in addition to music. There were of course the customary five-minute warnings before services and near the ends of breaks. Then there were the occasional surprises, such as the addition of overtime.

On this subject, Chicago had the most extraordinary rules. In fact, one category of overtime was known as “extraordinary overtime”! But that was only the most lucrative of the overtimes. There were also normal overtime, unscheduled overtime, and penultimate overtime. The crown jewel was extraordinary, and it was reserved for so-called “sacred” time periods such as the break between an afternoon rehearsal and evening concert. Like a nuclear weapon, it existed mainly as a deterrent. Should a conductor deploy the extraordinary option and incur its obscene costs, he would surely be blacklisted from future engagement with the orchestra. It was mutually assured destruction, in contract form.

At the time I was a member, the first five minutes of extraordinary overtime paid approximately $75 per player. The next five minutes doubled the pain: $150. The next five? You guessed it: $300 per player. Unfortunately for the players, the progression stopped there rather than continuing logarithmically until each musician could afford to hire his own conductor with acceptable time management skills!

Any time a conductor had bungled things so badly as to run out of time before running out of music, we would begin shooting glances at each other: will it happen? Extraordinary? Most of the time, of course, rehearsal would simply end, and we’d be left to live off our wits at that evening’s concert, as with American in Paris. But every once in a while, the stars would align, and the personnel manager would rush onto stage at the appointed time, not to dismiss us, but to solemnly intone: “There will now be five minutes of extraordinary overtime.”

So put yourself in the orchestra’s shoes for one fateful day just before I joined the Chicago Symphony. The conductor in this story is impossible for me to forget, but because of his heroic act I will withhold his name. The program was a relatively routine French concoction, ending with a piece as routine as it was popular: Ravel’s Bolero. If any piece can be said to be sight-readable (assuming that the component parts are in place, as they most definitely were in Chicago), it’s Bolero. Therefore it was no surprise when the conductor, as was his habit, ran out of time before rehearsing it. The usual glances were dispensed with; it was simply assumed that Ravel’s least favorite piece would get the slapdash evening reading to which it was accustomed.

But it was not to be. The personnel manager walked out with an air of uncertainty, and after a hushed conference with the maestro, announced: “There will now be twenty minutes of extraordinary overtime.” Audible gasps gave way to wheels turning inside each orchestra member’s head (keep in mind that before the smartphone era, math actually had to be done there or on paper): more than $800 per player, to rehearse Bolero. With a full orchestra on stage, it would cost Ravinia’s management close to 100 times that amount, on par with the conductor’s fee for the week!

Now, since overtime charges are sometimes deducted from those fees, my colleagues came up with an intriguing scenario: the conductor, ashamed of his own incompetence and realizing the superiority of the musicians surrounding him, had selflessly engineered a socialist redistribution of wealth. Through his Bolero scheme, Ravinia’s money went not to the top 1% but flowed instead to the other 99%. It was beautifully designed. But after that concert, the revolution was over. We (the workers) never controlled the means of production, as evidenced by all the Elliott Carter works we played in the ensuing seasons.

A more predictable rhythm

In my eight weeks at Ravinia that summer, I played twenty-four classical programs: the equivalent of some orchestra’s entire seasons, and more symphonic music than I had played in my entire life up to that point. Therefore the return to Orchestra Hall and the downtown season was most welcome: a ten-minute commute rather than an hour, actual practice rooms, and just one program a week.

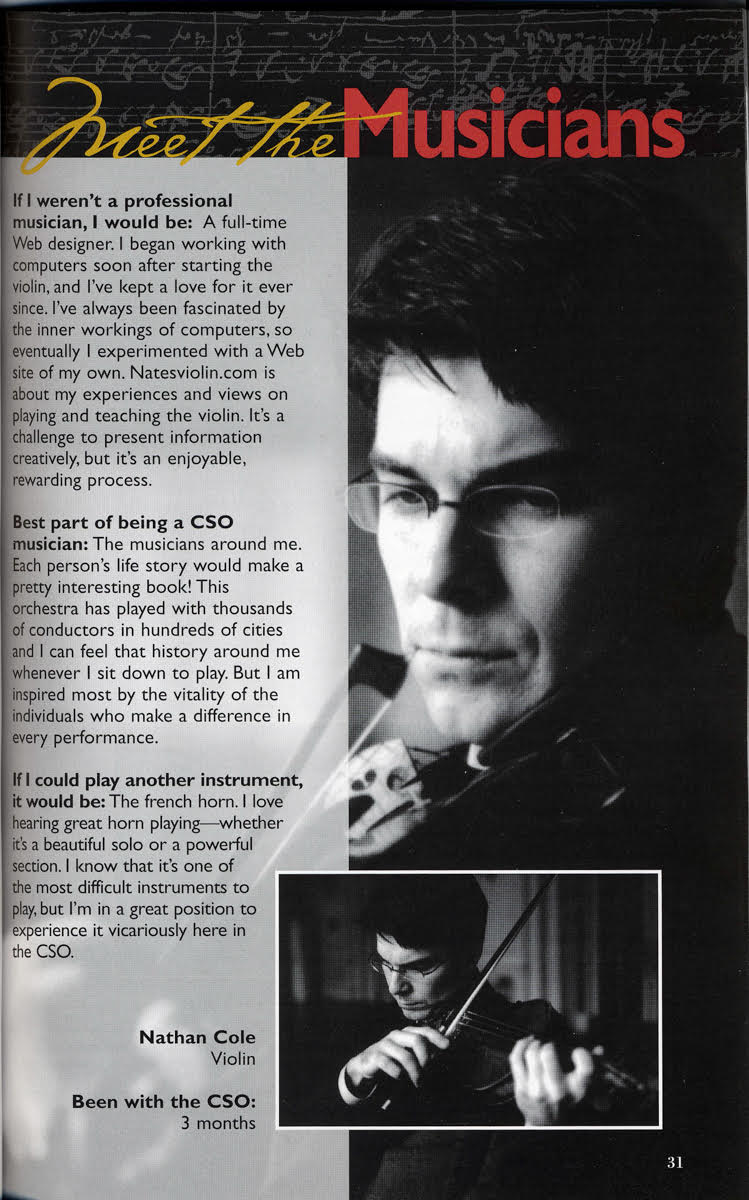

Sometime during that first full season with the orchestra, I was featured on the cover of the program book, with a brief Q & A inside. Apparently, if I hadn’t been a violinist in the Chicago Symphony, I would have been a web designer! I was working on my website, natesviolin.com. Not much has changed, in the end.

A picture from my apartment that season sums things up nicely. For some reason I felt compelled to arrange a still-life of my main interests: my violin case, complete with metronome and tuner; my practice journal, with Parker fountain pen; and my 4×5 Wista field camera. In the background, you can see the enormous boxes that used to come with video and DVD-mastering software. Maybe things have changed after all: my metronome and tuner now reside on my smartphone; my journal is on my Mac; my 4×5 film sheets have been replaced by my digital SLR; and nobody buys giant software boxes anymore.

Just keep your balance

If I had to pick one moment from that first season in Chicago that will live forever in my memory, it would certainly be the first sounds I ever heard from Pinchas Zukerman. Barenboim was on the podium, and the two of them were both dressed in soccer apparel. Just as it was during my very first week, Elgar was on the program: the magnificent violin concerto, which puts unusual demands on the orchestra. The opening tutti is full-blooded and symphonic, and I had my hands full following its twists and turns. Therefore by the time it wound back to its original material, I was unprepared for the soloist’s entrance. Zukerman, at the peak of his powers and playing a gorgeous Guarneri del Gesu, was like a lion at ease. He roared without giving the slightest impression of effort. I stared open-mouthed, neglecting to come in with the section several bars later.

At that moment, I knew that as long as the Chicago Symphony was the place to hear violin playing on that level, Chicago was the place for me. The collective confidence of Barenboim and Zukerman can hardly be described: for the two of them, rehearsal was a distraction that could be dispensed with as long as the entire stage was on their wavelength. I needed to know how two artists could be so comfortable not only in their own performances, but in their collaboration, night after night. I looked up from my stand as often as I could get away from the notes.

I almost didn’t make it onto stage for the first performance of the Elgar. As it was the second half of the concert, and there was a substantial stage change during the intermission, we had to stay off stage until all was set under the lights. Once it was safe to take our seats, we began filing onto stage. Just before I passed through the narrow door, I tripped and nearly fell flat on my face (and, needless to say, the Strad). It was not a simple loss of coordination: something, or someone, had tripped me! I looked back, and there against the wall, mostly concealed in shadow, was Barenboim. His mischievous grin removed all doubt as to who had been the culprit. Be ready for anything.

Nathan Cole, First Associate Concertmaster of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, is one of the world’s leading coaches for the violin audition repertoire. Previously a member of the Chicago Symphony and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, he has sat on audition committees for nearly every orchestral instrument. He has also performed as guest concertmaster for the orchestras of Houston, Minnesota, Oregon, Ottawa, Pittsburgh, and Seattle.

Nathan’s passion is helping violinists reach their potential in the practice room, concert hall, and audition stage. Through one-on-one coaching, master classes, blog posts, and videos, he shares detailed knowledge that is typically taught only inside elite conservatories. His “New York Philharmonic Audition Challenge” invites violinists from all over the world to follow Nathan’s own audition preparation timeline. It has already been adapted for other instruments including flute and viola.

Born to professional flutists in Lexington, Kentucky, Nathan started violin at age four in a Suzuki program. He earned his Bachelor of Music at the Curtis Institute, where he spent less time practicing solo pieces than he should have, and more time rehearsing string quartets. His wife, Akiko Tarumoto, is Assistant Concertmaster of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

You can visit and write Nathan at www.natesviolin.com.

No Responses